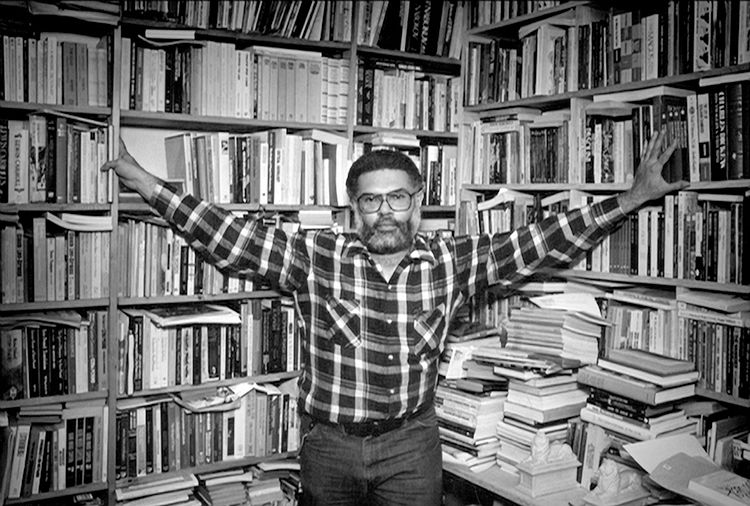

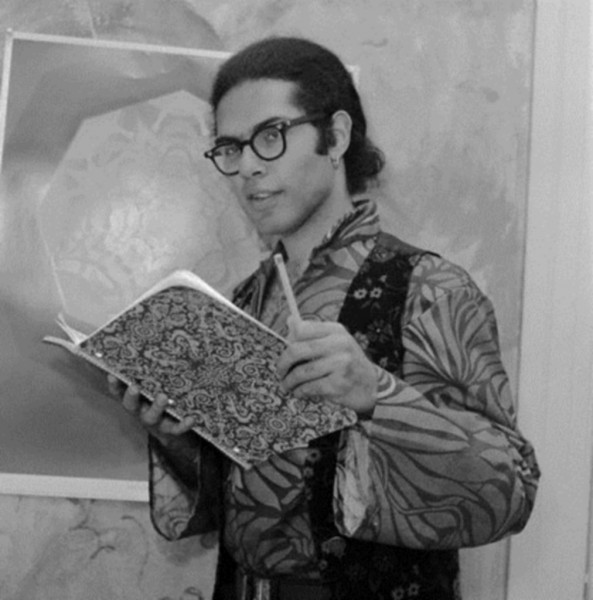

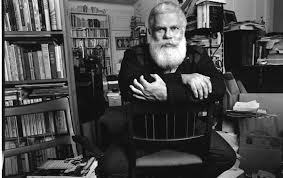

SAMUEL R. DELANY - EXCERPTS FROM THE PARIS REVIEW NO. 210

I think of myself as someone who thinks largely through writing. Thus I write more than most people, and I write in many different forms. I think of myself as the kind of person who writes, rather than as one kind of writer or another. That’s about the closest I come to categorizing myself as one or another kind of artist.

I was born in Manhattan. I grew up in Harlem, a block away from what was then the most crowded block in New York City, according to the 1950 census. Something like ten thousand people lived in one city block. Probably that means it was more crowded than Calcutta or Singapore or Yangon—places we think of as inhumanly crowded today. The city gets you used to crowds, used to people relating to one another in a certain way, like strong and weak interactions between elementary particles. The strong interactions only come into play when the particles are extremely close, less than the distance of a single atomic nucleus. Those are the interactions readers want to see in novels. At the same time, paradoxically, cities can be dreadfully isolating places. The Italian poet Leopardi wrote in a letter to his sister, Paulina, about Rome, that its spaces didn’t enclose people, they fell between people and kept them apart.

The whole discussion over the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, the notion that the lack of the word in the language means it’s all but impossible to entertain the concept, while a detailed vocabulary, such as the Inuits’ fifty-plus words for fifty-plus different types of snow—powdered, crusty, hard, soft, blown-into-ridges, et cetera—enables you to perform intellectual feats of winter negotiations unthinkable to temperate-climate folks like you and me.

What’s wrong with the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis is that it fails to take into account the whole economy of discourse, which is a linguistic level that accomplishes lots of the soft-edge conceptual contouring around ideas, whether we have available a one- or two-word name for it or only a set of informal many-word descriptions that are not completely fixed. Aphra Behn clearly describes the “numb fish” and its calamitous effects on other fish, animals, and human beings, so that we all recognize it as what we call the “electric eel” today. But she did it in the mid-seventeenth century, well before anyone had thought of electricity or Franklin had sent his kite up into the lightning storm. Thus falls the Sapir-Whorf.

Discourse is a pretty forceful process, perhaps the most forceful of the superstructural processes available. It’s what generates the values and suggestions around a concept, even if the concept has no name, or hasn’t the name it will eventually have. It determines the way a concept is used and the ways that are considered mistaken. The following may be a bit too glib, but I think it’s reasonable to say that if language is what allows us to think things, then discourse is what controls the way we think about things. And the second—discourse—has primacy.

For a couple of years in my early twenties, I was a die-hard believer in the Sapir-Whorf, though I had never encountered the term, or even read a description of it, which begins to hint at what’s wrong with it as a theory. I even wrote a novel that hinged on the concept—Babel-17.

Perhaps the largest problem the lack of a single term imposes is that it becomes difficult to individuate the idea. Where does it begin and where does it end in terms of what it refers to out in the real world? The more complex verbal support there is for a concept, the easier it is to critique.

If I’d had the term Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, it might have been easier for me to realize that it was just incorrect—in the same way that when, at twenty-one, I first encountered the word dyslexia, I was able to realize I wasn’t the only one with these problems, that it was a condition rather than an individual and personal failure on my part, and the stories I’d read about writers such as Yeats, who didn’t learn to read until he was sixteen, or Flaubert, who was so backward in his reading and writing that he was known as l’idiot de la famille, now made much more sense. The realization of the flaws in the Sapir-Whorf, in that they caused me to begin considering the more complex linguistic mechanisms of discourse, you might say gave me my lifetime project.

It goes back to the notion that what happens in the mind of the reader when the reader moves his or her eye from word to word on the page—that’s what a story actually is. What the language calls up in your mind can also make you think in a rich and vivid manner. How it makes you think about what it evokes, including its place in the world—that’s particularly important. And how it makes you think about it must be supported by certain discourses. If those discursive models are rich enough, they inculcate the sophisticated idea of discourse itself that I’m striving for. For forty years, that has been and remains my project.

Frequently, those discursive models are in conflict with simpler discourses. When that happens, for some people it will be as interesting and as exciting as a good chess game. Others will not pay that much attention to the discursive conflicts. For them it’s not so interesting. But, as I did, listening to the students after my MIT lecture and reading what some of them went on to write me about the experience, I have the impression that a certain number were hungry for the kind of experience they had there and took from it something I can recognize as what I’d wanted to give. It’s not a message, but an experience of seeing the world and the topics it comprises at a certain level of complexity, of potentiality, of relationship—a complexity and relationship that intricately entails, even as it empowers, the pursuit of beauty and joy.

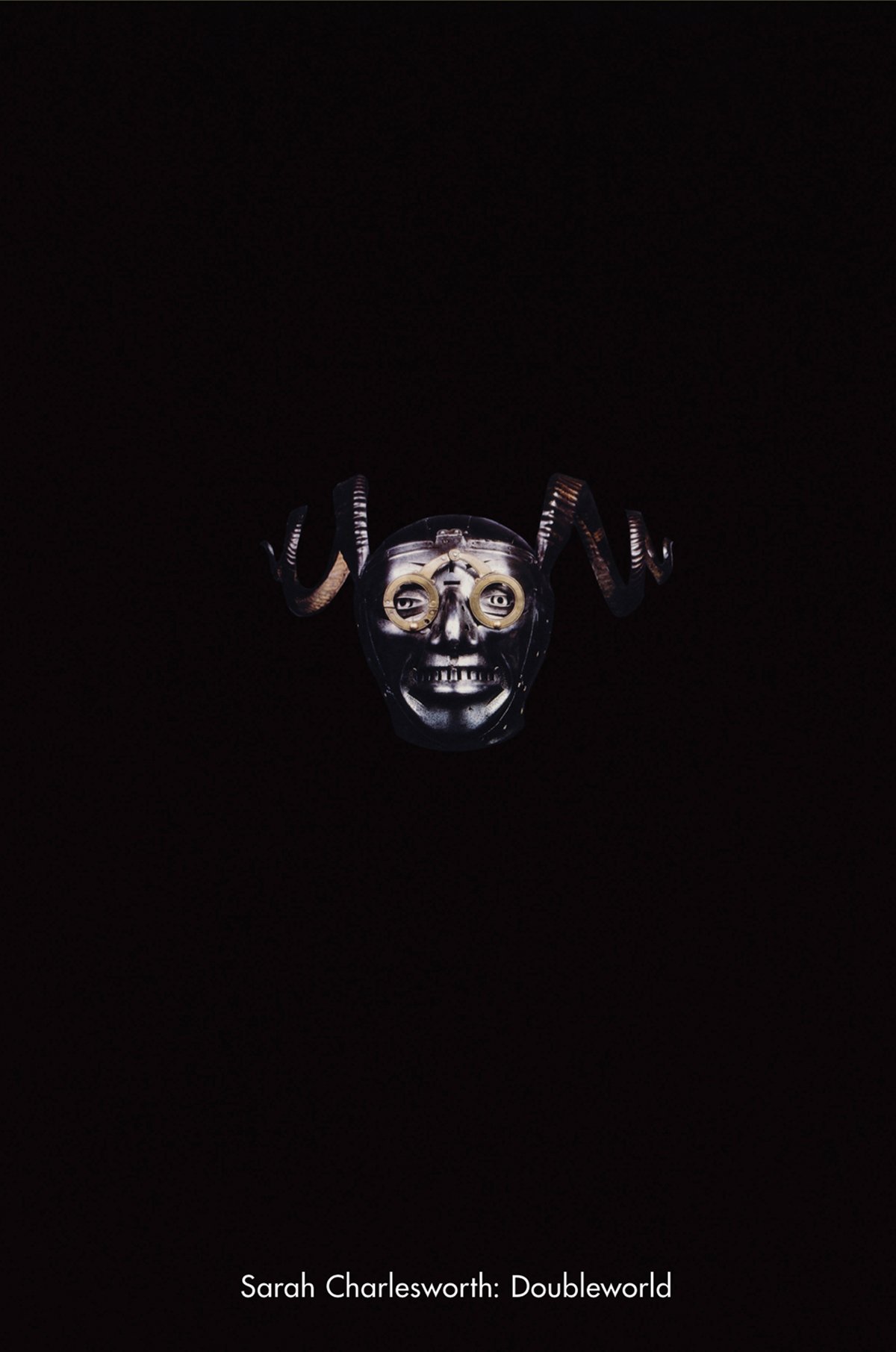

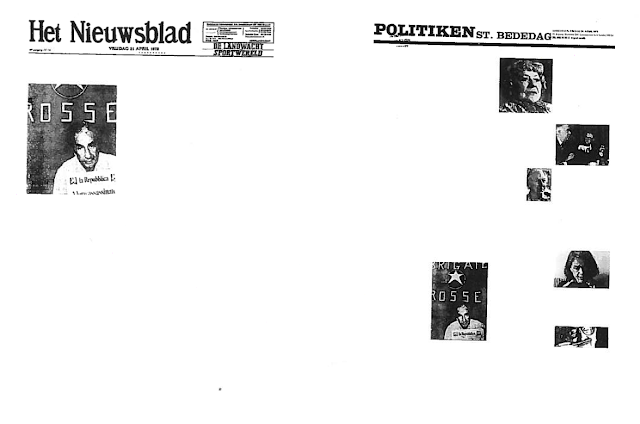

Sarah Charlesworth / From DOUBLEWORLD

"To live in a world of photographs is to live in a world of substitutes--stand-ins--representations of things, or so it seems, whose actual referents are always the other, the described, the reality of a world once removed... I prefer, on the other hand, to look at the photograph as something real and of my world--a strange and powerful thing--but not a thing to be viewed in isolation, but as part of a language, a system of communication, an economy of signs."

...

"The pieces are deliberately extracted, context-less. I think that this is exaggerated by the fact that I often don't remember what culture some object that I've used comes from. This is very much a postmodern amnesia. There's a deliberate kind of, I don't know that you could call it "denial," but certainly an ignoring of what the initial context is and a recontextualizing. That's the way that images function in mass culture, and I'm trying to exaggerate that. They stand for things, and we don't need to know exactly where they came from. We use them for what we want them to mean.

Well, I think that "real history" is a fiction anyways, so I'm exaggerating that fiction. Certainly, an Egyptian statue in an Egyptian museum, studied by an Egyptologist, has a difference significance than the "Egyptian" figure that I've used. I don't know of whom the statue is, Amenhotep IV or something like that, or from what dynasty it comes. I just call it "The Sphinx" because that's how it's going to function in my vocabulary. It admits a question but not a clear answer. I think of myself as a robber or something. I plunder and pillage on paper. I like the fact that I can have anything I want out of all time and place (that I can get via image form) as mine. I possess these things and give them my own meaning. This is very different from what an art historian does, which is to try to approach some description of what the original meaning was. I'm using images that are available in my culture, and I'm using them for my own purposes in order to describe a state, a cultural state, a state of mind, that is meaningful to me."

...

"In one sense, we live in a regular three-dimensional physical world, and in another sense, we inhabit an entirely different image-world. While the three-dimensional world and the image-world are physically distinct, there is a kind of conceptual osmosis, a reciprocity of meaning between the two. The image repertoire that is yours and mine via popular culture is something we share: a common vocabulary. It's the commonality of the landscape that I'm describing, not a private mindset.

Images of the first man on the moon, or images of President Kennedy being shot, or fashion photos, Calvin Klein ads, these are certain images that are part of our "real" environment. I think that what we're so awkwardly approaching is a totally different state of culture than that which we've previously known. It's a metaphysical problem. I wonder about the true metaphysical state of living with images that are shared and propagated by the hundreds of thousands. Part of the feeling we have, you and I, of being inarticulate in approaching these issues is that we, in fact, lack the vocabulary. We lack the conceptual structure. Over and over again, I'm talking about problems of representation, and I can barely get through the elements to stand still long enough to talk about them."

...

"Even when Walter Benjamin talked about "Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction," he was talking about multiple copies versus unique objects. We are not even talking about multiple copies. We are talking about the global, electronic, computerized, satellite-dish transmission of images, reaching millions of people. Images themselves are traveling at the speed of light... well, at least, sound. This is an entirely new, not only metaphysical frontier, but a political and social frontier. We're pioneers in terms of trying to approach a conceptual grasp of what it means. Culture itself has become abstracted to the point where its extremely difficult for a person to even conceive of the way in which they exist in it. We live in a transcultural state wherein culture itself has become self-conscious of itself as culture. It's abstraction already.

Compare this with a more localized culture in which you have your set of traditions and costumes and food. We choose between Chinese or Italian for dinner, or whether to wear our Japanese designer clothes or read our French philosophy. We live in a "hyper-" (or "meta-") culture that borrows geographically and socially from a number of different (originally local) cultures that have become almost free-floating in a media culture. I don't belong to an authentic, original culture. If there's a way to describe my culture, it's as a pop culture, which is a metaculture."

...

"It sounds imperialistic, but all I'm taking are pieces of paper, which are already mine by virtue of the fact that they are on my floor or worktable. I bought the magazines. Once they are transmitted into my environment, I allow myself the freedom to react to them, to respond to them, to alter them, in keeping with my own desires, directed toward the human goals... the values I support."